The word ‘co-elaboration’ seems to exist only in esoteric research sources in English, although in French it appears to be more common. The senses of ‘elaboration’ meaning to develop, to add detail to, and to make beautiful all coalesce to make co-elaboration a word with multiple meanings that riff on a tune; working together to make something greater than the sum of its parts in some sense. A beautiful, creative something. A something in which different people take turns with the baton, to stand on the shoulders of others, to spark off one another’s ideas and enthusiasm in the spirit of innovation. A ‘something’ because no-one is necessarily sure what it might look or feel like yet or even what category it might be in: a process, a paper, a product, a partnership, a plan.

Last month, many of these things and plenty more were discussed as we hosted the inaugural ISDDE (International Society for Design and Development in Education) UK meeting; part of a wider plan to have more local symposia between the large international annual conferences. At the two days of discussion and presentation on design in mathematics education Lynne McClure and the team at Cambridge Mathematics hosted representatives from NUI Galway, Mathematics Mastery, University of Nottingham Shell Centre, MEI, Cambridge Assessment ARD, NCETM, Cambridge Assessment International Education, Cambridge University Press and Autograph.

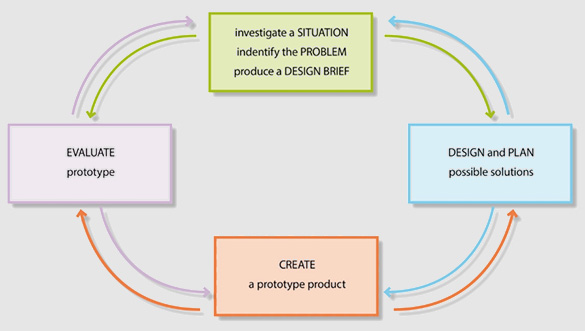

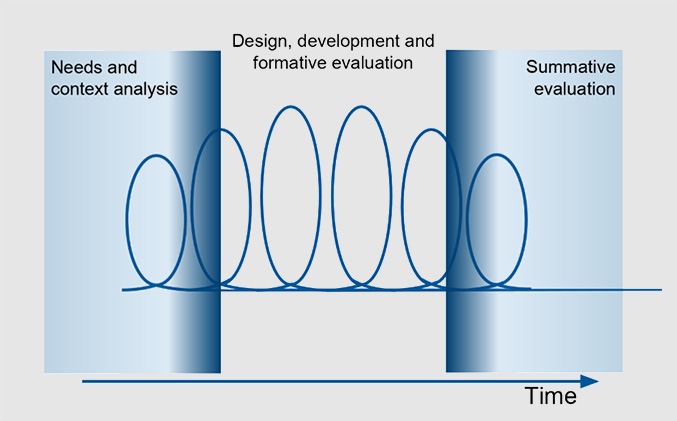

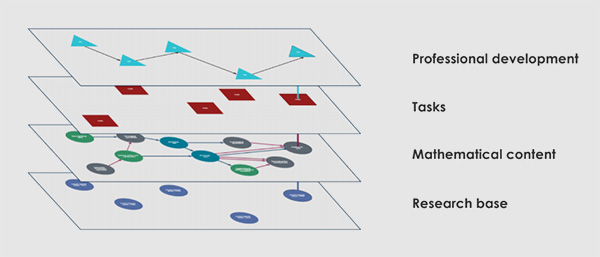

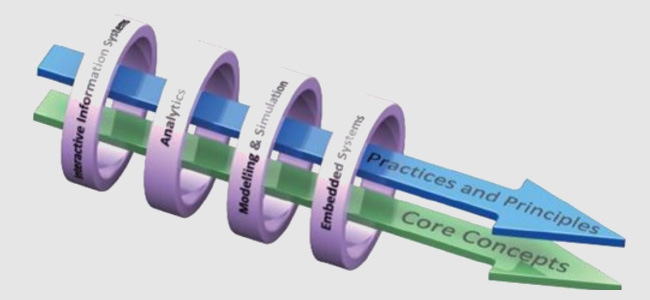

The brief for the two days was to consider theories of learning, design intentions and fidelity, and other emergent issues-in-common. The broad range of organisations present meant that we could consider not just theoretical ideas around design research, but the very messy and pragmatic issues of how to design in practice: for real classrooms with real learners, for real teachers with real time constraints, for real customers with limited budgets and attention spans, because ‘an essential feature of educational design research is the development of solutions to problems of practice’ (McKenney & Reeves, p.19). Interestingly, everyone present had (at least one) model for learning as part of their design criteria or principles: we heard about ladders, chains, steps, runs, bricks, spines, maps, buckets, routes, funnels, hopping, sloshing and jumping-off. Then there were the similarities in design cycles, with iterative, repetitive models being common to all there in some respect.

Source: https://www.ncca.ie/media/3369/computer-science-final-specification.pdf

Source: https://www.mathematicsmastery.org/

When you think of designing professional development, tasks, books, interactive activities, frameworks, software, curricula or programmes of learning, how do you conceptualise routes and progressions in your head? How do the loops and twists of finding out information and using that information compare to the ways in which we do this in the classroom with formative assessment, adjustment, returning to first principles and initial questions and assumptions? And how might the idea of co-elaboration – sharing knowledge and learning from one another’s mistakes – apply equally, too?

One thing that so many participants remarked upon over the two days was the remarkable similarity of the challenges, constraints and struggles that they faced, despite often working in such different areas. An important consideration was how we could move forward with the sharing of solutions to these struggles in order to develop a community of co-elaboration with the common interest of making maths education better for all. What changes to the way that organisations share research, design processes and problem-solving could you envisage that might help overcome some of the most common reasons for failure in design – those at the strategic level?

Join the conversation: You can tweet us @CambridgeMaths or comment below.