There was muted expectation around the OECD launch this month of the Mathematical Literacy Framework, upon which the 2021 Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA) tests will be based. Here at Cambridge Maths however, where our core work is designing a maths Framework, we were very keen to see what the international experts had devised.

The first PISA study was published in 2001. Each study is worldwide, although not every country chooses to take part. They take place every three years and are intended to be a way of evaluating educational systems by comparing the performance of 15-year olds in mathematics, science and reading.

Image source: https://pisa2021-maths.oecd.org/

The emphasis of the 2021 PISA framework is on mathematical literacy (defined as ‘the capacity of students to reason, analyse and communicate ideas effectively as they pose, formulate, solve and interpret mathematical problems in a variety of situations’1 ), rather than mathematics itself. It is intended to measure and compare ‘how effectively countries are preparing students to use mathematics in every aspect of their personal, civic and professional lives, as part of their constructive, engaged and reflective 21st century citizenship’, which suggests the focus is as much on the use of mathematics as knowledge of mathematics.

How does this play out? Mathematical content is identified through six key understandings which permeate four main topic areas. Reasoning and problem solving have high prominence, as one would expect with an increased focus on use. Different contexts are identified: personal, occupational, social, and scientific, with the last keeping the door open for problems within mathematics. There is a recognition that technology plays an increasing role in all aspects of life and that students should be confident in using and interpreting digital mathematical information. A new section refers to the importance of embedding computational thinking within maths: decomposition, pattern recognition, generalisation and abstraction, and algorithm design.

PISA is increasingly used in the process of national education policy making and seen as an important indicator of system performance; most countries – irrespective of whether they perform above, at, or below the benchmark PISA score – have begun policy reforms in response to PISA reports. This means that PISA assessments have increased the influence of this (non-elected) commissioning body2 through serving as external accountability for national system performance. Rey (2010)3 goes so far as to suggest that the PISA surveys, interpreted as objective, are actually promoting specific orientations on educational issues. We know that, when at the DfE, Michael Gove warned that ‘ignoring what PISA tells us in education would be as foolish as dismissing what control trials tell us in medicine. We would be flying in the face of the best evidence we have of what works’; although Nick Gibb, the current schools minister takes a different view. In a recent interview he commented that ‘they are pushing a particular, progressive approach to education, the 21st-century competence-based curriculum…it’s almost assumed that you want to have a competence-based curriculum; and I talk to other education ministers from around the world, including some from the developing world, who have been advised by the OECD to go down this route that we know doesn’t work.”4

Some questions arise here. Firstly, is it correct to state that the PISA framework is a competence-based curriculum? Secondly, what evidence do we have that our current (non-competence-based) model does work? In the same week where we have been told that 35% of students failed to achieve a grade 4 in Maths and English, are we adequately preparing all our students for the next phase of their lives?

Related questions concern the implications of this piece of work for mathematics education policy here in the UK. In 2022, when the results of the first tests based on this new framework are published, will there have been changes in national policy aimed at the UK improving our score and/or position in the international league table? Do we already sufficiently embed reasoning and problem solving – within those real-world contexts of the social, personal, occupational and scientific – in our curriculum and assessments? Is there sufficient opportunity for digital engagement? Where is computational thinking currently enacted, and where could it be enacted?

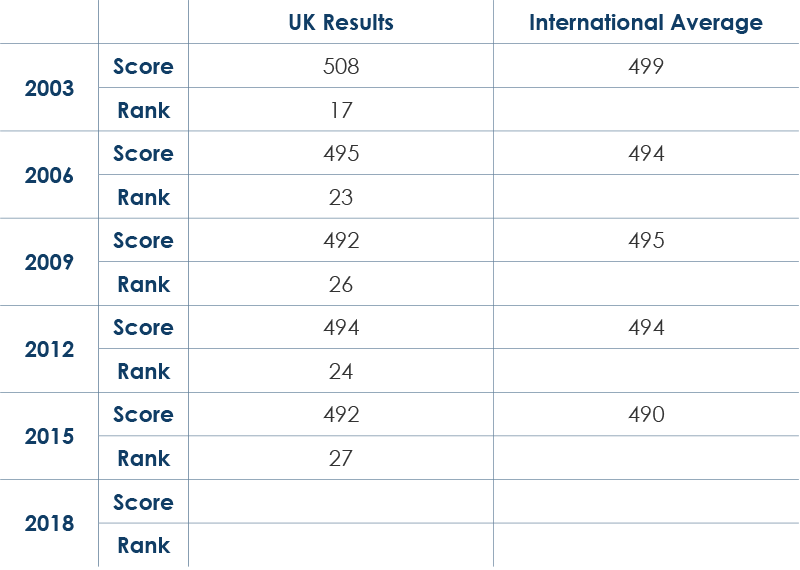

The results of the 2018 tests are due to be published on 3rd December this year. It will be interesting to know a) how well the UK performed, in absolute and comparative terms, and b) what the official response will be. Watch this space…

References:

1http://www.oecd.org/education/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/33707192.pdf

2https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programme_for_International_Student_Assessment accessed Oct 2019.

3Rey, O. (2010) The use of external assessments and the impact on education systems, in CIDREE Yearbook 2010.

4https://www.tes.com/news/gibb-attacks-too-political-pisa-rankings-body.

Join the conversation: You can tweet us @CambridgeMaths or comment below.